Youthful Innocence During Hard Times.

Welcome to the first of AFFCAD UK’s 50 Ugandan Asian Exodus Stories. This story is by Purvy, one of our Trustees, who along with her family had to flee Uganda like so many others.

Purvy was just five years old when she left her home in the southern Ugandan town of Jinja. Having left at such a young age, her memories of childhood in Uganda are few in number; however, the memories she does have are joyful, and held securely in her mind.

After a distressing voyage away from everything they’d known, Purvy and her family continued to face a variety of hardships in unfamiliar territories. But, by sticking together and remaining positive, they managed to build stable and prosperous lives from scratch in their new home: London.

This is Purvy’s captivating story.

A happy childhood in a beautiful country

“I can’t remember a lot of my life in Uganda, beyond vague memories of certain places; but in my head, the country was an idyllic place that brought me a sense of peace and happiness. When I think of my hometown, Jinja, I think of sunshine, glorious green shades of trees and bushes, and red soil. I remember the sweet smell of rain which would stop as suddenly as it started. People living there didn’t seem stressed, and life seemed easy.

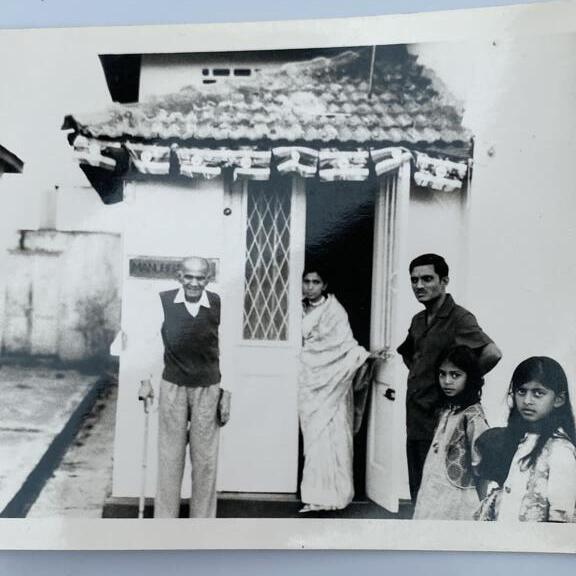

Perhaps this was because my family owned a business called African Ironmongers, through which we were able to live comfortably. Three families were supported by one shop, which I remember as we resided directly above it. The business was founded by my grandfather, who previously worked as a railway station guard before predicting that there would be a great need for materials in the developing nation of Uganda. He was right.

I often wandered into the shop downstairs to see what my father was up to; but aside from this, I didn’t do a lot with my time as a five-year-old girl in Uganda. I ate, slept, laughed (and probably cried too)—I enjoyed my simple little life. In particular, I do recall spending time on one street named Gabulla Road, because my sister used to have a group of friends who referred to themselves as the ‘Gabulla Road Gang’. I would often tag along behind them all, as they found me too irritating to include in their activities (but this didn’t bother me much!).

Another memory I have of life in Uganda is going on lovely picnics by the lakes with my family. We could see hippos and hear their roars while we ate our food. Whenever we went for a lakeside picnic, there were usually so many of us that we would fill up a few cars on the journey there. People always did things in groups, and I really enjoyed having people around all the time—it made life interesting, and there was always someone to talk to.

Indeed, the community spirit seemed strong—everyone knew everyone. However, at the time, I didn’t realise that we were actually segregating ourselves from the native Ugandan population. I was too young to understand all that; I simply assumed that families were very large groups of people (not just four in a house), and that it was normal for family members to move freely between each other’s homes. You didn’t get invited; rather, you just popped into each other’s homes unannounced. I did like the fact that there was always someone to talk to, but I don’t think I comprehended how claustrophobic this lifestyle could feel at times, because it was all I knew.”

An abrupt and confusing change of circumstance

“On an otherwise typical day in 1972, I remember coming home to find the place in a total mess, with suitcases, crockery and household goods scattered everywhere. It’s unsurprising that I felt so confused: Jinja was a quiet town and it felt like everything moved slowly, so when things changed all of a sudden, it was a lot to process. Moreover, when I was little, Indian families like mine never really explained anything to children. We just tried to put the pieces together ourselves, or eavesdrop on adult conversations.

Of course, there were plenty of adult conversations being held, about an evil man called Idi Amin who was telling us that we had to leave our home in Uganda. I knew of him because I’d seen him on TV before. I could tell that he was very important, and I found him scary. Through the lens of the tranquil life I’d been living, I couldn’t compute much more than that; I was too young to understand politics, or who did what to who and why. As these events were unfolding before my eyes, I didn’t grasp how drastically my life was about to change, and that it would never be the same again.

In hindsight, I consider myself lucky to have been so young at the time, because it must have been really scary for the adults. My family was about to lose everything, and they knew that they would have to start from scratch in an unfamiliar environment—meanwhile, I was sheltered from these fears. In fact, the utter turmoil around me felt like some sort of adventure. I was curious about the frantic behaviour and the suitcases littering our flat. I listened intently to the constant talking, and understood that my large family was splitting up to fly to different parts of the world. London was mentioned often in these conversations, and I knew that I was headed there. Although I suspected something bad was happening, I lacked the sense of urgency that, by contrast, the adults must have felt so strongly.

I never said goodbye to our domestic help, nor to my home. There was no final walk through the flat, no feelings of nostalgia, and no sadness. I simply grabbed my teddy bear—a first birthday gift from my father, and one which I’ve kept safe to this day—and off I trotted, in ignorant bliss, away from the life that I’d known. After all, I’d failed to grasp that we wouldn’t be coming back. Maybe I was a slow learner, or maybe that’s how well my parents and the other grown-ups around me protected their young. Indeed, I don’t recall seeing any tears fall from their eyes, and they showed no fear.

It wasn’t until we reached the airport to leave Uganda that I felt any sense of danger. Throughout the terminal, I saw men wearing army uniforms and carrying rifles. At one point, one of the immigration officers snatched my teddy bear from me, and I screamed and cried as they cut open the bottom of the bear to check if we’d hidden anything inside the toy. Asians were known for their love of gold, and since we weren’t meant to be taking such valuable things with us, the officers were thorough when it came to checking our bags.

Little did they know that the gold was actually sewn into my mother’s petticoats, which were worn under her saree. Sewing was a skill possessed by all of the ladies in my family; and in fact, all of them had strategically sewn their jewellery into their petticoats. I remember watching them use the sewing machine to do this, and listening to them talk about it. I thought it was strange, but then again, there was a lot of equally strange behaviour going on at that time. For example, I wondered why we were filling up big metal trunks with our crockery and household items, questioning whether we’d really need so many things for this adventure! Against my better judgement, it turned out that my mother certainly wasn’t going overboard with the packing, because we would later end up feeling extremely comforted to find these familiar objects while living in a very unfamiliar country.

My mother tried to calm me down while I wailed for the officer to return my teddy bear, and this was one of the rare instances when I noticed her looking anxious. Once I’d gotten it back, we made our way to the gate, leaving a trail of stuffing behind us. I remember trying desperately to keep my hand over the torn part of my toy, unaware that my teddy bear’s misfortunes were the least of our troubles. Nevertheless, I remember spending the flight from Uganda stuffing my face with Opal Fruits (which are now known as Starbursts)—I loved them, and they always seemed to make everything better.”

First stop: India

“My family and I flew from Uganda to India, where we’d planned to stay temporarily to settle my grandfather, who didn’t want to move to London; and from this point onwards, my childhood memories become much more vivid. I remember feeling awestruck at the size of my grandfather’s house, which was over three storeys—moving into this house from a two bedroom flat made it seem especially huge.

One of my earliest memories of living in India is my mother waking me up and handing me a large pot to take to a man around the corner who owned a cow and sold its milk. I did this regularly, and often felt paranoid making the trip back because sometimes stray dogs would bark at me, causing me to spill the milk and get into trouble with the grown-ups. Being expelled from my home in Uganda didn’t scare me, but going to collect milk from around the corner certainly did! Although, as usual, Opal Fruits would often save the day.

India was strange to me at that time, not just because most of my regular family members weren’t there, but also because it brought a new way of life to which I was unaccustomed. It looked, smelled and felt different—not quite like home in Uganda. However, one thing that hadn’t changed was the constant flow of visitors through the house, many of whom would often whisk me away and bring me back before dinner. (Safeguarding issues were much less of a concern back then.)”

Family unity in a new home

“Eventually, my family and I left India to settle ourselves in London. The day we made the journey there was a very exciting one for me, because I would finally be reunited with all of my relatives who had travelled to London ahead of us. I’ll never forget what I said the moment we arrived at Heathrow Airport, nor will a few other people—especially my uncle. He was the only one of my relatives who’d managed to own a car by then, for which I should’ve afforded him praise; but when I saw his Ford Cortina parked and ready to bring us to our new home from the airport, I could only ask: “Where is the Mercedes?” To this day, whenever I’m reminded about this incident, I shudder—what a brat I must have sounded like! It was at this moment when I started to realise that the lives of my family and I were going to be very different moving forward. And yet, this realisation only added to my excitement because, after all, I was still under the impression that it was merely a trip—not a total upheaval of our lives—and that order would be restored fairly soon.

When we reached the house, it felt great to see my sister, cousins, uncle and aunt. (One of them wasn’t even my aunt, but in Indian culture almost everyone older than you is your aunt or uncle, even without blood ties.) At that time, the house sheltered three families between four bedrooms. Suffice to say, not everybody had a proper bed: the living and dining rooms both had makeshift beds in them. Interestingly, I don’t remember any of us ever fighting for the bathroom or toilet—we all simply managed. How thirteen people avoided conflict with one toilet and one bathroom is beyond comprehension for my children; nowadays, we quarrel over two bathrooms, even with far less of us under the same roof! Perhaps there’s a lesson there about the difference in values between today’s kids and my generation.

Living in that house, my family went from strength to strength, and together we formed an abundance of happy memories. One could describe that period in our lives as being a lot like the song Hakuna Matata: with good food and nice clothes, I never felt as though I lacked anything, and the atmosphere was always cheerful. The elders did such a good job of providing for us that I didn’t know we were actually just renting that house.

More critically, I didn’t understand how lucky we were to have a home to go to at all. It’s only later that I learnt about the thousands of other Ugandan Asians who ended up in army barracks, otherwise known as camps. Many families had been split up against their wishes, not just within the UK but between different countries. I didn’t realise that not everyone had the funds to buy plane tickets, and had to leave their families behind in India and travel alone to the UK, hoping to earn enough money so that they could be reunited with their loved ones.

I credit my blissful ignorance to the seniors of the house, who bore the brunt of the hardships we experienced following the exodus. They knew what they’d lost, and faced the challenge of moving to a country that was socially, culturally and politically unfamiliar to them head on—all the while refraining from showing any negative emotions. (In fact, to this day, they have never talked about their own fears, worries or stress.) Rather, with love and laughter, they stuck together; put the collective family above their own individual desires; and protected us children as best they could. Their behaviour was remarkable, and something that I can only truly appreciate now, as I was too young to do so back then. What an amazing generation.

Back in Uganda, the seniors worked hard and ran their own businesses, which meant that the ladies at home didn’t have to go out to work—although I think they worked harder at home than they would have at any job! In London, though, my real aunt, who was educated and confident, managed to get a job as a receptionist at our doctor’s surgery. Our doctor was Indian, so all of the Asians in the area flooded to her door. It was, therefore, very handy to have my aunt as the receptionist (although in those days, it was much easier to get an appointment to see the GP). Meanwhile, my mother started taking steps towards integrating herself into our new location: she began wearing western clothes, and landed a job in a factory. Rather than buying lunch from an outside vendor, she would save money by bringing a lunchbox to work instead.

My father also found work, and I remember his excitement when he returned home with his first brown envelope of hard-earned cash. Equally, my real uncle, who was a true man of the world, would work at a fish and chip shop during the lunch break of his main job. This way, he got a free meal, but also earned extra money, which I recall he saved to buy a bottle of whiskey. (He didn’t think it was right to use family resources to buy his treats.) My uncle—who used to wear Italian suits, with combed-back hair like Clarke Gable, and fly around with high society friends in private jets—was reduced to this. However, in the same fashion as the rest of my family, he never let on if this new way of life saddened or humiliated him. He simply got on with whatever life threw at him. I greatly admired him, and I wish I’d told him that.”

Hardships of youth

“My family and I built a life at home that was truly joyful, but going to school in London was a rude awakening for me. The challenges began on day one when, for some reason, I wasn’t placed into the special education classes that had been created for Ugandan Asian ‘refugees’, as we were often referred to. The children in these classes spoke little to no English, and hence couldn’t keep up with the pace of normal British lessons. Naturally, I didn’t always understand what was going on while attending the main classes.

Suffice to say, I stood out from the other kids in my class, which brought on some additional social challenges. One day in particular, I remember hearing all of my classmates start laughing, so in response, I laughed too—that made them laugh even more. I suspect that they were saying silly things about me, to see if I could understand them. But it wasn’t long before their mischief no longer worked on me, because I loved to talk and learnt English quickly.

Unfortunately, though, the teasing didn’t end there. One thing I didn’t understand until much later was a strange sound that other kids would constantly make as I walked down the school corridors—it was a way of ridiculing my accent and different manner of talking. I also found it bizarre when other kids would ask me if I ate curry and if that was why I smelt, because my mother didn’t cook curry (in fact, I didn’t even know what curry was), and I didn’t smell. Surprisingly, since then, curries are among the UK’s most popular dishes—it’s funny how times have changed.

On the topic of food, I remember finding school meals challenging to get down, as they were more bland than the food I was used to eating. Apart from salt and pepper, school meals came with no other condiments.

Despite these struggles, I liked attending my school, and I made plenty of friends. So it was a shame when, just as soon as I started to feel truly settled in there, I transferred schools. This was because two of the families living at my house—mine included—moved to a different location; we’d saved enough money to buy a new house (and a new Ford Cortina) in the north-western London suburb of Kenton. I thought it was great, though, as it felt to me like we were moving into a mansion, despite the fact that we’d still be sharing one bathroom and toilet between nine of us.

I don’t think the quiet neighbourhood we moved into knew what had hit them. We were the first Indian family on our street—and what a chaotic family we were. Our neighbours’ conception of a Sunday family lunch was four to five people, plus a grandparent or two; meanwhile, ours was a meal for twenty-five. Local residents were mystified by the constant stream of people in and out our door; and I imagine that they were never quite sure how many people actually lived at our house.

It was only following this move, and hearing my family talk about buying a business here in London, that I realised this truly was my home now. It had taken me seven years to actually accept that we weren’t going back to Uganda.”

Finding success and giving back

“When you go through something like being expelled from your country, I suppose it’s natural to often wonder what life would have been like if you’d never left. I prefer to focus on what I can do with my life in the present, while keeping the memories of Uganda that I do have close to my heart. After all, I may not have achieved so much if I hadn’t come to the UK: I was able to finish my education and go on to university, from which I graduated with a BA and MA in Politics. Although it’s not the medical or accounting career path that was expected of me, I’ve been able to stand on my own two feet, through my successful career in marketing. I’ve worked for many blue chip organisations, such as BT, BP, SKY TV and, more recently, Age UK—the largest charity in the UK for giving support to older people.

I’ve always felt an intrinsic pull towards older people—perhaps because I grew up away from my grandparents. So beyond my work at Age UK, I volunteer as an in-person and telephone befriender through the Methodist Housing Association, supporting isolated and lonely seniors. ’Live at Home’, as the scheme is called, enables elderly people at a local level to continue leading independent lives in their homes, instead of going into care.

In fact, nowadays, my career has taken a back seat to my charity-related endeavours; I devote more of my time and energy to charities, as a way of giving back when so many have given to me in the past. In particular, I’m the Vice Chair of the Board of Trustees for AFFCAD UK—a young charity based in both Uganda and the UK. Here, I provide strategic marketing expertise and governance, directing funds from grants, partners and donors towards supporting the charity’s school and educational programmes in Bwaise—the biggest slum in Kampala, Uganda.

I’m also an active fundraiser for the Vraj Charitable Trust, for which I provide direction for fundraising and community events. Every year, I spend eight days in India working as ground support for projects run by the trust over there.

Meanwhile, on Sundays, I don my wellies and go to work on a charity-owned ISKCON organic farm, which grows a wide range of produce and supports free food distribution. I help with organising local volunteers, and I act as the Team Leader for various community events. I’ve also commercialised our approach to asking for funding, by producing business cases for large greenhouses and irrigation systems that demonstrate the farm’s impact.

Additionally, before working on the farm, I volunteer for Vallabh Youth Organisation by teaching a group of teenagers about Hinduism and related culture, using an international curriculum. We aim to assist our students’ understanding of the importance of integration, as well as their own cultural heritage and individuality.”

Reliving the past

“My life in London has certainly been fruitful and fulfilling; but occasionally, I’ve found myself longing for Uganda in my heart. Certain moments have left me missing the little things that made Ugandan life what it was for me growing up. For example, I remember my first time drinking passionfruit juice here in the UK, which I adored back in Jinja (alongside matoki and cassava chips). When my cousin and I learnt of a place nearby that was selling passionfruit juice, we drove there so fast that it was like a car chase scene from The Sweeney, hurtling around the corner to treat ourselves to a glass. Tasting the sweet and ever-so-familiar flavour of passionfruit was like going back in time for a moment.

An even more profound experience for me was when I actually revisited Uganda, about twenty-eight years ago. Another cousin of mine who was living in Kenya drove me across to Uganda, and it was an amazing trip. He took me to my old home, and the families living in the flat at the time were very welcoming, letting me look inside. It felt strange being back there after so long, and it didn’t look like I’d remembered it—but the experience gave me an invaluable sense of closure, and I’m so grateful to my cousin for his part in that. Moreover, at one point during the trip, rain suddenly pelted down on us and we got soaked, before the sun came out just as quickly and dried us in true Ugandan style. In my head, I can still smell the sweetness of the ground when this happens—it’s a treasured memory of mine which is lodged in my brain.”

We hope you enjoyed the first of our 50 Ugandan Asian Stories. This is a project by AFFCAD UK to celebrate the 50 year anniversary of the exodus of Ugandan Asians, by collating and archiving the stories of those involved. If you would like to contribute a story, do get in touch here.